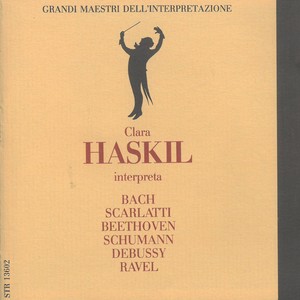

Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Robert Schumann, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel: Clara Haskil interpreta...专辑

Clara Haskil2019-05-03

专辑简介

CLARA HASKIL In Ludwigsburg in April 1953 Clara Haskil gave a truly exceptional recital. The programme was an unusual one for a great pianist in that epoch, in that it didn't include only 18th and 19th century works, or a homogeneous selection of 20th century pieces. Lipatti was another exception in this sense, and one is constantly reminded of him as one listens to Haskil's playing, reproduced here with great fidelity. To begin with Bach was considered a du-ty, and it was non easy matter exposing oneself to comparison with Fischer, who for years had set a very high standard in concert halls all over the world. Clara Haskil's Bach has a slightly unusual quality, perhaps because today we are more familiar with the sort of sound produced by Gould and Richter in Bach. Nonetheless, this Toccata appears in a new light, almost as if it had lain under a layer of dust until Haskil, with natural spontaneity, said: Now, I play it this way. The Scarlatti is one of the highpoints of this CD. Simple phrases, sounds that flow magically, and a singular concentration that transform these brief phrases into impressive and complete solo pieces. One should really have the courage to explore these performances in greater depth to discover the intimate nature of the relationship which the pianist established with music, to grasp the mystery world of art. It is quite natural to ask one-self how much of this message has remained alive today in the concert halls, remembering that in the same period Horowitz too gave us his tense, brilliant and technically masterful reading of Scarlatti. Times have changed too much for us to reply without lapsing into nostalgia, but it is certain that the true Scarlatti emerges from the fingers of a humble performer whose whole life is dedicated to art. Who meets this description better than Clara Haskil? Beethoven makes his appearance with the masterful sonata opus 111. It is too big a jump (Mozart, in fact, is missing) not to disconcert the listener. After a series of brief and self-contained pieces the listen-er has to cope with a complex and highly articulated work which requires consid-erable concentration and mental flexibil-ity. As a Beethoven pianist Haskil requires no introduction, yet this piece is so prob-lematical that one would require a life-time to come fully to grips with it. The opening attack is on a grand scale and securely managed, but an unexpected error then reminds us brutally of the fallibility of live recordings and of the fact that even Clara Haskil was a human being and therefore subject to errors. As the performance procedes, however, its impressive weightiness gives us the impression that music and performer are fused in a single world of thoughts and sentiments; the single parts lose all importance alongside the coherence of the whole. The single phrases, at times sad, at times aggressive, at times overwhelming, are woven into a whole almost as if Beethoven was speaking directly to men of all epochs. This was one of Haskil's greatest gifts: she retained entirely her own character whilst revealing the profoundest thoughts of the composer. As with Bach and Scarlatti, it would have been marvellous to compare this interpretation with Lipatti's. It would perhaps give us a still deeper realization of how much we have undervalued Clara Haskil. Only recently have we begun to appreciate the great subtlety of her pianism. The sonata opus 111 is like a door open on life: to those who remain without it reveals the intimate greatness of Beethoven's spirit, while for the composer himself it represented an opportunity to convey his deepest reflections on man's place in a world that was changing profoundly and was later to generate the entire culture of the 19th century Shumann's Theme and variations opus 1 is a little performed piece, although it contains the seeds of the composer's later works. It lacks both the flavour of German Romanticism and the sinuous freedom of Schumann's mature piano compositions, like the Kreisleriana, Carnaval and Novelletten, which would astonish the world and win a place among the very greatest works of art. This piece is beautiful for the way it is played by Haskil, who infuses all of her delicate soul into the rather formal and academic notes, just as Dino Ciani was to do, many years later, when he trans-formed the much more complex Novel-letten into pure poetry. Both in late Beethoven and early Schumann the pianist is always in complete control of the instrument, conveying sounds and thoughts in perfect balance yet sacrificing none of the fascinating uneasiness of the artist. There follows a jump to the post-Romantic period and the notes of Debussy's Etudes. Clara Haskil plays with Mozartian grace and introduces a new dimension to the composer's undefined and percussive style wich brilliantly under-lines the intimate coexistence of tradition and innovation in these works. The pianist seems to oscillate in her interpretative choices between formal preoccupations and the atmospheric sound effects which are so typical of the Etudes, giving the impression of not wishing to favour outright either of the two readings. The Ravel Sonatina brings us to one of Clara Haskil's greatest musical achievements. It is an extraordinary interpretation, a foundation stone of pianistic art, which sees in this piece (as did Walter Gieseking in masterly recording of all the works) as a point of no return. At the end of the Ludwigsburg recital Clara Haskil deserves rapturous applause. Our only regret is that Mozart is missing. Alberto Cantoni

专辑曲目

1

Sonatina for piano in F sharp Minor - I. Moderé

Clara Haskil2

Sonatina for piano in F sharp Minor - II. Mouvement de menuet

Clara Haskil3

Etude livre 2, for piano - I. No. 10, Pour les sonorités opposées

Clara Haskil4

Sonatina for piano in F sharp Minor - III. Animé

Clara Haskil5

Etude livre 2, for piano - II. No. 7 Pour les degrés chromatiques

Clara Haskil6

Sonata, for piano in B Minor, K 87 L 33 - I. Sonata

Clara Haskil7

Sonata, for piano in C Minor No. 32 Op. 111 - II. Arietta, Adagio molto semplice e cantabile

Clara Haskil8

Tema e variazioni, for piano Op. 1 sul nome ABEGG - I. Tema e variazioni

Clara Haskil9

Sonata, for piano in C Minor No. 32 Op. 111 - I. Maestoso, allegro con brio

Clara Haskil10

Sonata, for piano in e flat Major, K 193 L 142 - I. Sonata

Clara Haskil11

Sonata, for piano in C Major, K 132 L 457 - I. Sonata

Clara Haskil12